Mystery Of History

by Marc Jacobs

Although Filipino Martial Arts are among the most popular fighting systems in the world, their origins are obscure. There is quite a bit of informative material on the subject, but most of what one reads about the roots of Kali, Arnis, Escrima and so on are either conjecture passed off as fact or in some cases pure mythology. So instead of just repeating these myths, I will present what is actually known about the origins of the FMA and offer a few new ideas about how they might have evolved.

At the outset, it should be noted that what we consider FMA - those weapon-based arts found mainly in the northern and central islands of the Philippines - share many similarities.

share many similarities. This could indicate a common influence, but does not necessarily mean that they have a common origin. Such an influence may have emerged in recent years, after the arts had become established.

As for origins, we know from Spanish documents that the inhabitants of what is now the Philippines had some form of fighting capability since at least the 16th century. Case in point, Filipinos offered armed resistance to early European explorers such as Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521).

However, almost all societies at the time possessed some degree of combat ability with weapons, which means that this is not evidence of advanced martial arts skills, let alone anything necessarily resembling modern FMA. The earliest Spanish accounts actually describe the use of arrows and spears, but these are not necessarily typical of modern FMA . Beyond that, we know little about what pre-Hispanic fighting methods looked like in the Philippines.

We do know, however, that a great deal of Spanish terminology is used in modern FMA. Although this may suggest that Spanish colonizers directly influenced Filipino martial arts, it is unclear how widely Spanish was spoken by the majority of people in the islands before the 20th century. Numerous Spanish words have long been part of the native Filipino languages, and this could indicate a Spanish origin for some of the techniques in FMA. However, it could also just indicate the general influence of the Spanish language on local Filipino dialects.

FENCHING

Both Spanish fencing and FMA use a sword-dagger combination - something that is not common outside of classical European fencing. Aside from a handful of traditional Japanese kenjutsu styles that use the long and short sword together, there are almost no other examples of the combined use of sword and dagger. This may indicate some sort of Spanish influence on FMA, at least as far as Filipino "Espada y Gaga" training is concerned. Researchers Ned Nepangue, M.D., and Celestino Macachor have presented some compelling circumstantial evidence that Spanish swordsmanship was indeed a foundation for the development of what became modern FMA.

While Martinez does not completely rule out the possibility of a Spanish influence on FMA, he says that if such an influence existed, it probably came about through Filipinos trying to imitate European fencers rather than through direct instruction.

So while the influence of classical European fencing on FMA is possible, it is by no means certain. But does a Spanish influence on FMA necessarily have to come from fencing, or could there have been other sources of inspiration?

THEATER

Another possible source of Spanish influence is the performing arts-particularly the Spanish "moro y cristiano" plays, which sometimes depicted conflicts between Muslim and Christian warriors through stylized sword fights. Local versions of these plays were performed in both the Philippines and Venezuela, so imitation or direct learning of the theatrical fighting style may have influenced both forms of stick fighting. Indeed, several Filipino styles claim that their arts were traditionally "hidden" in such shows (called "moro-moro plays" in the Philippines) and passed on in this way. But so far there is no direct evidence that Filipinos actually copied any fighting methods used in plays.

More recently, however, beginning in the late 19th century, we know that at least some prominent mestizos (upper-class people who had Spanish and native Filipino ancestors), including Filipino revolutionaries Jose Rizal and Antonio Luna, trained in modern forms of European fencing. While there are also claims that they practiced indigenous FMA methods, there is no historical evidence for this to date, and such claims may be the product of nationalistic mythologizing. It is possible that these men learned some form of FMA, but the only available evidence shows them practicing Western fencing. At least one of these figures (Luna) is said to have founded a club to teach European fencing.

We also know that Lorenzo Saavedra, the founder of the first club now claimed to have publicly taught FMA in 1920, allegedly trained with a French fencer while in prison. Interestingly, Saavedra's Labangon Club and the Doce Pares Club that later grew out of it were originally called fencing clubs. However, present-day FMA practitioners maintain that the use of the term "fencing" in the original titles of these organizations was merely the result of following American conventions and that the clubs taught indigenous Filipino martial arts, not Western fencing.

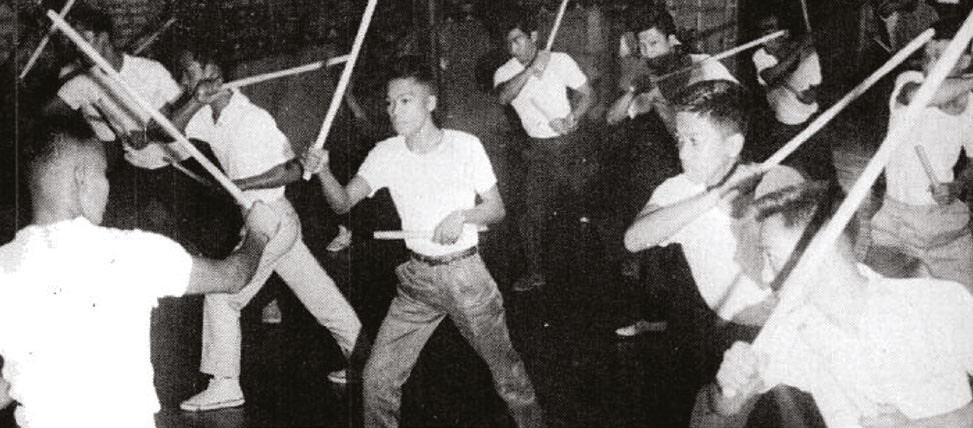

Unfortunately, there appears to be no photographic or other evidence of what exactly these early fencing clubs practiced, other than that they used sticks. But whether they used sticks in the manner of modern FMA is unclear. In fact, there is no historical evidence of them practicing anything resembling modern FMA in the early 20th century.

ARNIS

Incredibly, there is also no direct evidence of anything like modern FMA from before World War II. Even the limited documentary footage showing Filipino battalions undergoing bolo knife training with the U.S. Army during the war cannot be considered a definitive depiction of modern FMA. In fact, the earliest indisputable evidence showing what we now consider Filipino martial arts does not come until 1957, when Placido Yambao and Buenaventura Mirafuente published the first book on arnis. Although the word "arnis" has been mentioned before, notably in an early 20th century Filipino poem, it is not clear exactly what it referred to. According to FMA researcher and author Mark V. Wiley, the term, originally arnis de mano, was used in theater and not to refer to a specific martial art.

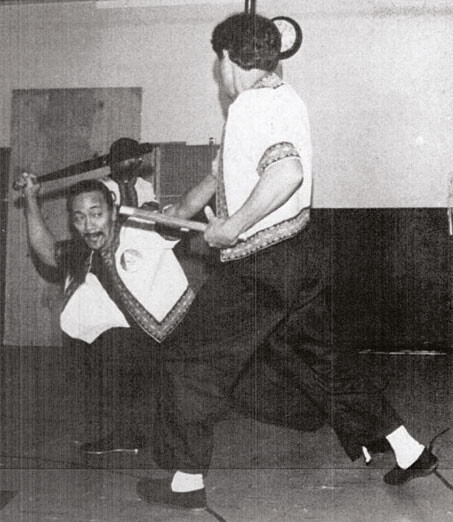

This is not to say that there is no evidence to suggest that martial arts were practiced in the Philippines during this era. There are photographs and films of Moros, the Muslim inhabitants of the southern Philippines, demonstrating local methods of weapon use, even if it is in the form of dance-like performances. Many of these demonstrations focus on the use of the spear and shield, which are not characteristic of modern FMA.

And although the Moros were known for their use of swords in fighting American troops in the early 20th century, much of their fighting appears to have been with spears. Since the southern Filipino martial arts are referred to as silat and are typically thought to be descended from Indonesian silat styles, it cannot be said that these performances truly represent modern FMA or are even the source from which modern FMA originated.

CLASS

How is it possible that what we think of as the traditional indigenous martial arts of the Philippines remained completely undocumented before recent years?

Therefore, they were unable to document their martial arts practice. At the same time, Filipinos who were literate may not have considered the vernacular practices of the lower classes worthy of documentation. Therefore, there is no record of FMA being practiced at that time.

Although this explanation is possible, it is problematic in that it makes FMA the only significant group of martial arts still practiced anywhere in the world that is said to have roots going back at least to the early 20th century. Even in less developed countries where certain martial arts were practiced only by the lower classes in the early 20th century, there is some documentary evidence, often from Western travelers who took photographs or noted these arts in newspaper articles or diary entries. For example, there is evidence from the early 20th century of the practice of martial arts in then obscure areas such as Burma, Laos, and Thailand. Yet, no such documentation resembling modern FMA in the early 20th century has been found. This leads us to at least consider the possibility that what we consider FMA simply did not exist before World War II. But if that is the case, what did exist in the Philippines during that time? Anthropologist and FMA historian Felipe Jocano Jr. believes it is because before World War II, these arts were largely practiced by the lower classes, people who were typically illiterate and did not have access to photographic equipment.

ROOTS

In his comprehensive and well-researched dissertation entitled "Filipino Martial Arts and the Construction of Filipino National Identity," Professor Rey Gonzales discusses how there were two schools of martial arts instruction in the Philippines in the early 20th century. One he refers to as the "old school," which used weapons in a performance-based manner, either through traditional dances, theatrical shows, or solo demonstrations of martial skill. This method may have roots that go back to the 20th century, although it is not known how far back they really go.

This is in contrast to what Gonzales has called the "new school." It began with the establishment of commercial fencing clubs in the Cebu area of the Philippines in the 1920s. But both Gonzales and Wiley acknowledge that it is uncertain exactly what was practiced in these clubs. Although descendants of the early organizations say the clubs taught traditional FMA methods, which they claim to practice to this day, as Gonzales documented in his dissertation, there is a lot of myth-making and historical revisionism among modern FMA practitioners. So today's accounts of what FMA was like 100 years ago cannot necessarily be taken at face value.

CONCLUSIONS

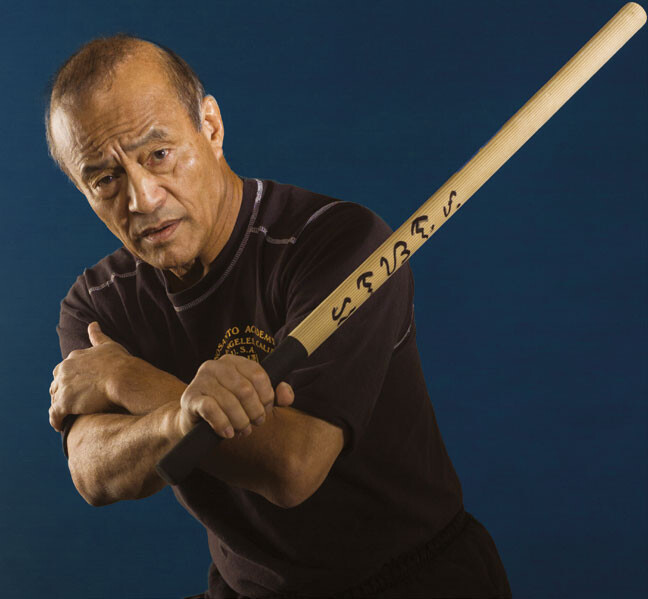

One point that has already been mentioned and needs to be addressed again is the similarities between most FMA styles today. On this subject, Gonzales contends that it is actually a relatively recent development that has manifested itself within the last 50 years - as the result of attempts to create a sense of Filipino nationalism among the various groups that inhabit these islands. He also credits Filipino-American martial arts pioneer Dan Inosanto with having a significant influence, as he trained with many teachers. In addition, Inosanto is said to have coined the term "Filipino Martial Arts" to refer to these fighting methods in a uniform manner. Of course, none of the theories presented here are definitive. They are merely possible explanations to help us better understand the still mysterious genesis of a group of popular martial arts.

Mark Jacobs' latest book is "The Principles of Unarmed Combat."

His website is writingfighting.wordpress.com